Every morning before breakfast, no matter the weather, the ninety-one-year-old Frederick Ayer could be seen taking his horse for a brisk twenty-five-mile canter. His friends and family described him as a Spartan, “a man among men” who moved about with a certain ease, common to those who have nothing left to prove. Hard work and discipline had always been the hallmark of the Ayers, beginning with grandfather Elisha Ayer Sr., who never enjoyed a day’s rest but would live to be ninety-six years old.

The Morning Union – August 8, 1913

The glow of his skin and the vigor of his limbs would put many a younger man to shame. Mr. Ayer has always been a great believer in open air and sunshine, and in the simple life. Horseback riding has ever been a hobby. He says his morning constitutionals in the saddle have perpetuated his youth and prolonged his life.

Born in Ledyard, Connecticut, in 1822, Frederick’s childhood ended just three years later when his father passed away and he was left in the care of his grandparents. He started picking sticks and stones on the farm, then drove the cows to pasture, brought lunch to the men working on the fields, and cared for the fickle Merino sheep his uncle had brought from Spain. As he longingly watched the neighborhood children skate on the nearby frozen lake, he wanted “money – some of my own,” so he began collecting animal bones to sell to the local button factory.

At sixteen, Frederick became a hoggee on the Erie Canal, having moved to Baldwinsville, New York, with his mother, her new husband, and three siblings. Always looking for better opportunities, he started working at Mr. Tomlinson’s country store in Syracuse around 1840, where his exceptional work ethic quickly earned him the owner’s trust and a management position within just one year. Aware of his business acumen, years later, in 1855, his brother James offered him a 1/3 stake in the J. C. Ayer & Co.

Upon his graduation from Westford Academy in Lowell, Massachusetts, James Cook Ayer began working as a clerk at the busiest drugstore in town. Within three years, he bought the thriving business, renamed it after himself, and introduced his first original product, Cherry Pectoral, a cold remedy that contained 1/16th of a grain of heroin. Once his brother joined the company to grow the business beyond the confines of the state and the country, James was able to focus on product development and marketing.

Too busy to even think about marriage, the love of Frederick’s life had walked into one of his Syracuse stores one day. On December 15, 1858, he married Cornelia Wheaton, with whom he had four children: Ellen Wheaton Ayer (1859), James/Jamie Cook (1862), Charles/Chilly Fanning (1865), and Louise Raynor (1876). Unfortunately, just two years after the completion of their dream home in Lowell and the birth of their youngest daughter, Cornelia passed away from cancer.

If the loss of his beloved wife was not painful enough, a mere six months after her death, Frederick’s brother James died as well. Work was the widower’s salvation, and he expanded his business holdings into the mills of Lowell and Lawrence. With his son-in-law, William Wood (husband of Ellen), he eventually established the American Woolen Company, a conglomerate of dozens of mills that would, at one point, become the largest in the world. While his business holdings continued to expand, so unexpectedly did his family.

Ellen “Ellie” Barrows Banning was an actress from a prominent St. Paul family whose history was as colorful as her personality. When she learned Edwin Booth would be performing Hamlet, she declined an invitation from one of the Wheaton sisters–Frederick’s in-laws– to have dinner with “a great catch.” However, after the show ended, “the handsomest man” walked up to her and asked if she was Miss Ellen Banning. Despite an age difference of over thirty years, Frederick and Ellie were married on July 15, 1884.

Ellie was a somewhat eccentric woman who created a world for herself and her family–Beatrice (1886), Frederick/Fred (1888), and Katharine/Kay (1890)–in which she was the leading lady. Despite sixty-five years of hard work, Frederick was not ready to retire when his doctors suggested he do so at the age of seventy-four; instead, Ellie suggested a break from business and the family moved to Paris for two years. Traveling across Europe for most of the time, six months were spent sailing down the Nile on a private dahabiya.

Upon their return to the United States in 1898, Frederick picked up his duties where he had left off and the family settled at Avalon on the North Shore, and a new home on Commonwealth Avenue designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany. It was in this home that George Patton would declare his love for Beatrice in 1908.

It is no wonder to me that you, and I may say Beatrice, have felt a growing admiration for each other, and I admire the delicate way in which you have treated the matter. Beatrice has a pretty well developed mature mind of her own and can speak for herself. Referring to your profession, I believe that it is narrowing in its tendency. A man in the army must develop mainly in one direction, always feel unsettled, and that his location and home life are, in a measure, subject to the dictation and possible freak of another who he may despise or even hate…

Frederick Ayer to George S. Patton Jr. – January 10, 1909

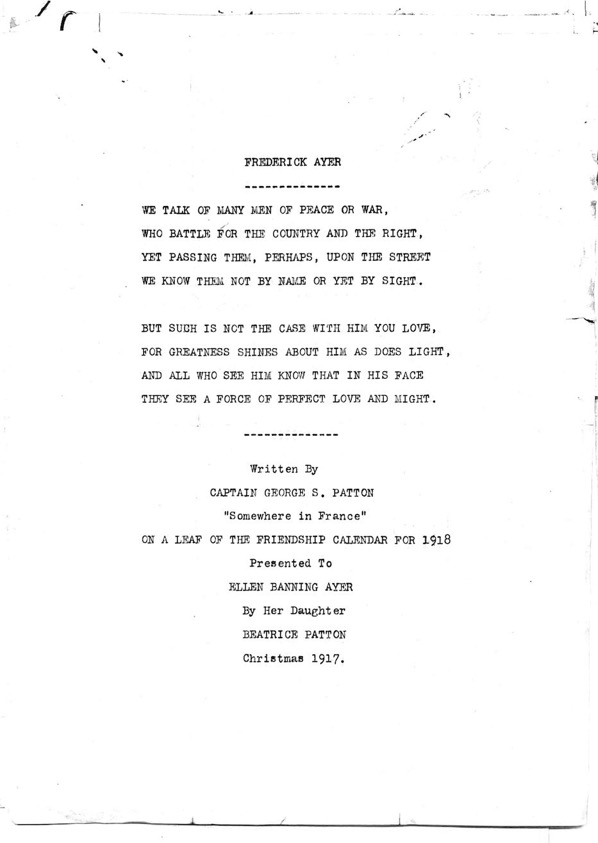

At first, Frederick opposed the marriage between Beatrice and George- he liked the man, but not the officer-but he eventually came to appreciate the youngster’s genuine love for his daughter and work ethic. Father-and-son-in-law were true believers in progress, and when Captain Patton was debating joining the Tank Corps during WWI, Frederick’s opinion was decisive.

Frederick’s philosophy was leading a “rational life of recreation blended with routine,” and Avalon was where he enjoyed a life of “wonderful vitality and activity.” Until a year before his death, he could still be found rowing on the lake or climbing on ladders to saw limbs of dead trees, and he went into the office at least three times a week. He only made two concessions to old age—taking breakfast in bed and dictating his letters as tremors affected his hands—but he remained a striking presence on his horse as he took a daily ride.

In January 1918, it wasn’t Newport–his favorite horse purchased in 1903–but the rain that felled Frederick. Confined to bed with a severe case of bronchitis, he never fully recovered and died on March 14, 1918, after “an acute attack of heart disease which lasted several days.” His wife Ellie died within the month, without a doubt of a broken heart.

Leave a Reply