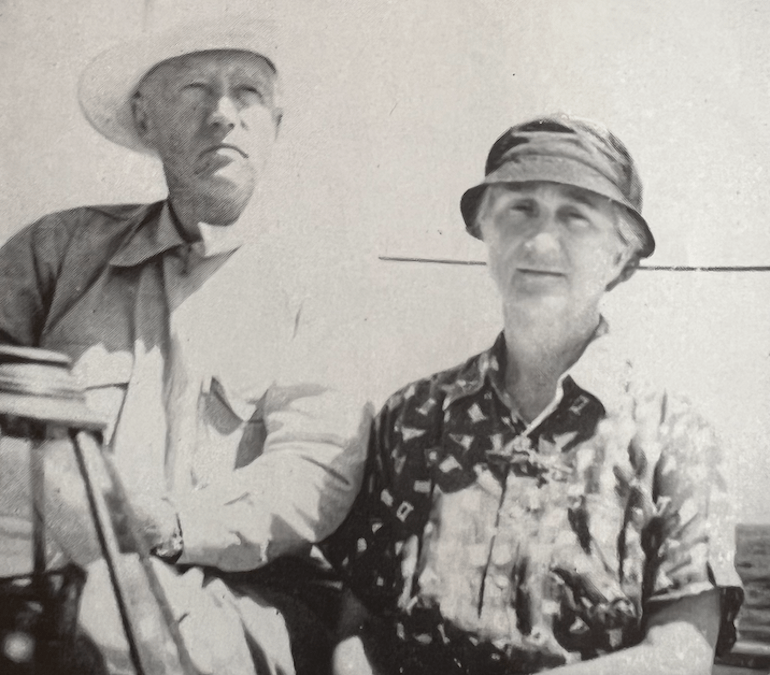

Since its founding in 1883, the National Horse Show had been the highlight of New York’s fall social season. The event drew the cream of American society, who attended the eight-day international jumping event dressed in tuxedos and evening gowns. During the 1930s, Beatrice and her daughters often occupied one of Madison Square Garden’s seventy-five viewing boxes as they watched George compete in the jumping competitions with the Fort Myer Horse Show Team. However, two decades later, on November 5, 1950, Beatrice watched the Spanish Riding School and its white Lipizzaner stallions, who were the special guests at the 62nd National Horse Show.

Born dark but turning their distinctive white (or, more accurately, grey) color between the ages of four and ten, the Lipizzaners were first brought from Spain to a stud farm in Lipizza (now Lipica in modern-day Slovenia) in 1580 by Archduke Karl Hapsburg. Three hundred and seventy years later, the stallions were visiting America, hoping to raise enough money to ensure the survival of the art of classical riding. Col. Podhajsky, the Spanish Riding School’s director, knew that “the graceful magic woven by the white horses could win friends and influence faster than any human could ever hope to.”

After the Lipizzaners wowed the audience with their caprioles, levades and courbettes — the ‘airs above the ground’ movements where the horse balances on his hind legs and leaps into the air — the lights dimmed across Madison Square Garden and the fourteen stallions pulled abreast as Col. Podhajsky alone rode forward on Pluto, a magnificent white stallion who years earlier “had cowered under a hail of bombs in Vienna under siege; had accepted reduced rations when food was scarce; had put up with rattling across war-torn Austria in an unadorned boxcar and stood without panicking during the horror of an unsheltered air raid outside a train station.”1

A red carpet was unrolled, and out walked General Tuckerman, the director of the National Horse Show, with Mrs. Patton, wearing a floor-length evening gown and carrying a bouquet of red roses. A single spotlight followed Col. Podhajsky as he dismounted Pluto and approached Mrs. Patton, “I am very happy to be able to show you the horses that General Patton, a great American soldier, saved for Austria.” Beatrice took a single rose from her bouquet and handed it to the Colonel as flashbulbs lit up the darkened Garden,

“I would give anything if only my husband could be standing here instead of me, for he loved the Lipizzaner so much.”2

General Patton’s role in saving the Lipizzaners from extinction at the hands of the Russians was only minor, yet his name would forever be linked with Operation Cowboy. When the Third Army was stopped at the border of Czechoslovakia as per the Yalta Agreement, they were a mere twenty miles away from the town of Hostau where a Nazi stud farm used Lipizzaner mares as part of a breeding program to create an Aryan race of horses.

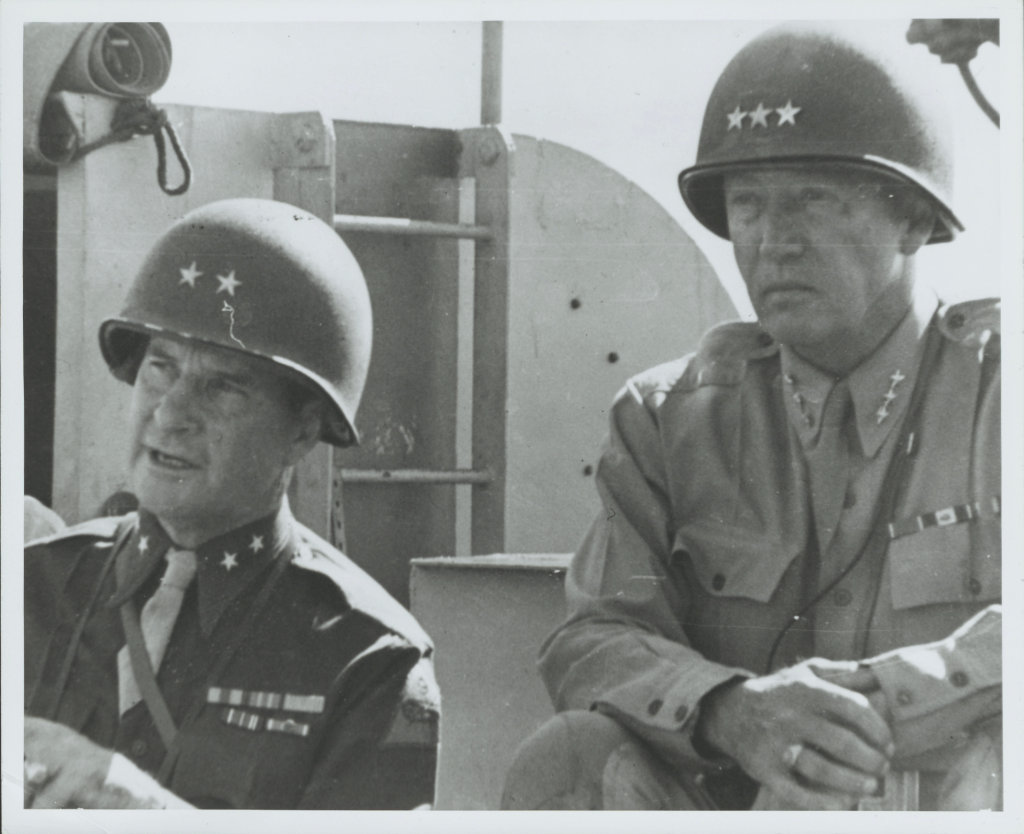

The mares were taken from Vienna in 1938 after Germany annexed Austria, but most of the stallions remained in the capital and were slaughtered by the Russians as they captured the city in April 1945. Worried about the safety of the mares with the Russians a mere forty miles away from Hostau, the German commander of the stud farm notified the Third Army that he and his men were willing to surrender on condition the Lipizzaners were brought to safety. General Patton approved the plan, and on April 28, 1945, an unlikely group of Americans, Germans, and Cossacks managed to bring hundreds of horses to safety despite fierce resistance from several Panzer Divisions at the border who remained loyal to the Third Reich.

A week after the Lipizzaners’ rescue, Col. Podhajsky gave a riding exhibition for General Patton and his men in Sankt Martin, Austria. Writing in his diary that evening, George wondered how “twenty middle-aged men in perfect physical condition, and about an equal number of grooms, had spent their time teaching horses tricks” while the world was “tearing itself apart in war.”

Beatrice, one of the few who had access to all of George’s papers, knew that as much as her husband loved horses, he thought there was “a place for everything.”

Leave a Reply